Help Defend Asylum

CGRS relies on the generous support of people like you to sustain our advocacy defending the human rights of refugees. Make a gift today!

For over two decades, CGRS has been at the forefront of the movement to ensure protections for refugees fleeing gender-based persecution. Professor Karen Musalo launched CGRS in 1999 following her groundbreaking legal victory in Matter of Kasinga, on behalf of Fauziya Kassindja, which recognized persecution motivated by gender as grounds for asylum for the first time in U.S. law. Founded to advocate for women like Fauziya, CGRS has grown into an internationally respected resource for gender asylum, renowned for our knowledge of the law and ability to combine sophisticated legal strategies with policy advocacy, grassroots mobilization, and human rights interventions.

We bring cutting edge litigation to push the law forward, advocate for policies that recognize gender-based persecution as a basis for asylum, and provide legal support in thousands of individual gender-based asylum cases annually. We also work with advocates and experts on the ground in the countries from which many asylum seekers hail, including Mexico, Haiti, and Northern Central America, to document and address the conditions that force women and girls to flee.

-

1996: Fauziya Kassindja, a Togolese woman fleeing female genital cutting, wins asylum with the representation of Professor Karen Musalo. This marks the first precedential decision recognizing gender-based violence as a basis for asylum.

-

1999: Professor Musalo founds CGRS to protect the rights of people fleeing gender-based violence.

-

1999: CGRS takes on the case of Rody Alvarado, a Guatemalan woman fleeing domestic violence. Her case becomes the battleground on the issue of whether domestic violence can serve as a basis for asylum.

-

2009: After a tumultuous decade of hard-fought litigation and advocacy, Rody Alvarado is granted asylum. This victory marks a turning point in the movement to secure protections for refugee survivors of gender-based violence.

-

2014: Aminta Cifuentes wins asylum in the first precedential decision recognizing domestic violence as a basis for asylum, known as Matter of A-R-C-G-. CGRS provides amicus support to Ms. Cifuentes’ attorney and trains advocates to apply A-R-C-G- in their clients’ cases.

-

2018: Attorney General Jeff Sessions personally intervenes in the case of Anabel (“A.B.”), a Salvadoran domestic violence survivor, using her case, Matter of A-B-, as a vehicle to proclaim that domestic violence and gang brutality “generally” are not grounds for asylum. CGRS takes on Anabel’s case.

-

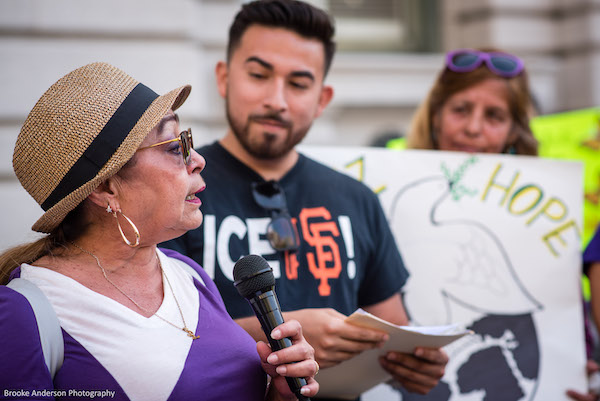

2019: CGRS and partners launch Immigrant Women Too, a national campaign to resist the Trump administration’s assault on asylum for survivors of gender-based violence. The campaign mobilizes asylum seekers and advocates in cities across the country, from San Francisco to New York City.

-

2020: Every major candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination pledges to overturn the Matter of A-B- ruling and restore protections for refugee survivors.

-

2020: The First Circuit overturns a lower court decision denying asylum to Jacelys Miguelina De Pena-Paniagua, reaffirming that despite the A-B- ruling domestic violence survivors are deserving of refugee protection under U.S. law. CGRS presents arguments in support of Ms. Pena-Paniagua as amicus.

-

2020: The Ninth Circuit reverses a lower court decision denying asylum to Sontos Diaz-Reynoso on the basis of A-B-, reaffirming that domestic violence survivors can qualify for asylum. CGRS presents arguments in support of Ms. Diaz-Reynoso as amicus.

-

2020: The Trump administration introduces draconian regulations that advocates dub the “death to asylum” rule. Among other provisions, the regulations sought to codify A-B- and permanently preclude protection for people fleeing gender-based violence.

-

2021: CGRS, along with co-counsel at the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program and Sidley Austin LLP, sues to challenge the “death to asylum” regulations and wins an injunction that blocks them from taking effect.

-

2021: The Biden administration issues an executive order pledging to issue regulations that clarify the refugee definition, with the intent of protecting the rights of people seeking asylum on the basis of gender-based violence and other human rights violations.

-

2021: The Ninth Circuit reverses a Board of Immigration Appeals decision denying asylum to Maria Rodriguez Tornes and affirms that domestic violence survivors can qualify for asylum. CGRS supports Ms. Rodriguez as amicus and provides expert testimony to corroborate her claims.

-

2021: Attorney General Merrick Garland vacates the Matter of A-B- ruling, restoring Matter of A-R-C-G- as national precedent for survivors of domestic violence seeking asylum.

-

2021-present: Post-vacatur, CGRS supports women whose cases were wrongly denied under Matter of A-B- in securing second chances to have their claims heard. CGRS and our partners successfully advocate for the government to provide this opportunity in hundreds of cases. In Matter of D-C-C-C-, for example, we convince the Justice Department to give another opportunity to a mother and daughter fleeing a Honduran gang that had murdered many members of their family; the agency had previously rejected their claims on the basis of Matter of A-B- and Matter of L-E-A-.

-

2022: Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Representative Zoe Lofgren (D-CA-19) introduce the Refugee Protection Act of 2022. CGRS endorses the bill which, among other crucial provisions, clarifies the legal standards for asylum to ensure people fleeing gender-based persecution have a meaningful opportunity to present their claims.

Clarifying the Law Through Regulations

On February 2, 2021, President Biden issued an executive order directing the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security to examine whether the United States’ treatment of asylum claims based on domestic or gang violence is consistent with international standards, and to propose a joint rule clarifying the meaning of “particular social group,” one of the five protected grounds upon which an asylum claim can be based. President Biden set a deadline of October 2021 for the rule to be proposed. Nearly two years later, the rule has yet to be introduced.

Many marginalized people request asylum on the basis of persecution suffered on account of their membership in a particular social group, including women fleeing domestic violence, children targeted by gangs, LGBTQ+ people fleeing homophobic and transphobic violence, and others who have been historically excluded from protection. However this area of asylum law has become highly politicized, with politicians promoting increasingly restrictive policies and legal interpretations that make it nearly impossible for many bona fide refugees to obtain protection. For those denied asylum, deportation can be a death sentence.

While some have proposed adding “gender” as an additional protected ground for asylum, this approach would not adequately protect women fleeing gender-based violence and would leave behind many others escaping persecution on the basis of social group membership such as LGBTQ+ people and children. It would also mark a significant departure from international refugee law as well as UN guidance, and could send a dangerous message to countries that have not codified gender as a separate ground that people fleeing gender-based violence do not otherwise qualify for protection - providing those countries cover to deny protection without meaningfully considering women’s claims.

Statutory Solutions

Lawmakers have proposed legislation that would clarify the legal standards applicable to asylum claims, combat bias and arbitrary decision-making, and ensure people fleeing gender-based violence and other human rights violations have a fair chance to pursue their claims. The Refugee Protection Act of 2022 clarifies several key terms that pose barriers in many meritorious claims, bringing U.S. law into alignment with international standards and guidance from the UN Refugee Agency. For example, it offers a definition for the meaning of “particular social group,” that would encompass “women” as a clearly recognized group, as well as the meaning of “nexus,” the requirement that an asylum seeker’s fear of persecution be linked to their membership in a protected group.

- "With Biden’s Asylum Ban, I Wouldn’t Be Here," Zoila, Ms., April 6, 2023

- "Her case ended in a joyful airport reunion, but the future of asylum is uncertain," Joel Rose, NPR, March 20, 2023

- "For Immigrants Fleeing Gender-Based Violence, a Long Road to Asylum in US," Tyche Hendricks, KQED, April 12, 2022

- "Deploring the Violence, Abandoning the Victim," Karen Musalo, Anne Dutton, and Mark Hetfield, Just Security, February 17, 2022

- "Woman Fleeing Domestic Violence Granted Asylum in US," Tanvi Misra, The Fuller Project, July 15, 2021

- "The Justice Department Overturns Policy That Limited Asylum For Survivors Of Violence," Joel Rose, NPR, June 16, 2021

- "U.S. Ends Trump Policy Limiting Asylum for Gang and Domestic Violence Survivors," Katie Benner and Miriam Jordan, New York Times, June 16, 2021

- "Central American women are fleeing domestic violence amid a pandemic. Few find refuge in U.S.," Paulina Villegas, Washington Post, June 13, 2021

- "Asylum and the Three Little Words that Can Spell Life or Death," Stephen Legomsky and Karen Musalo, Just Security, May 28, 2021

- "Domestic Abuse Survivors Fear Deportation Under Trump Policy Biden Has Yet To Reverse," Joel Rose, NPR, April 30, 2021

Get help

Get help Log In

Log In